Consensus Protocols: Paxos

You can’t really read two articles about distributed systems today without someone mentioning the Paxos algorithm. Google use it in Chubby, Yahoo used something a bit like it (but not the same!) in ZooKeeper and it seems that it’s considered the ne plus ultra of consensus algorithms. It also comes with a reputation as being fantastically difficult to understand - a subtle, complex algorithm that is only properly appreciated by a select few.

This is kind of true and not true at the same time. Paxos is an algorithm whose entire behaviour is subtly difficult to grasp. However, the algorithm itself is fairly intuitive, and certainly relatively simple. In this article I’ll describe how basic Paxos operates, with reference to previous articles on two-phase and three-phase commit. I’ve included a bibliography at the end, for those who want plenty more detail.

Why another consensus algorithm?

If you read my previous article on three-phase commit, you might be wondering why we need another consensus algorithm. 3PC does away with the main problem that 2PC has, which is its tendency to block on single node failures. In fact, the only way that I said that 3PC could have a problem was if the network was partitioned in two, and both partitions recovered an outstanding instance of the protocol to different conclusions, leading to an inconsistency when the network remerges. Is this really a significant enough problem to justify yet another consensus algorithm? Or is there some other problem which we haven’t yet acknowledged?

The answer to the first question may well be yes, depending on how pedantic you are feeling about your protocols. The answer to the second is definitely yes. 3PC works very well when nodes may crash and come to a halt - leaving the protocol permanently when they encounter a fault. This is called the fail-stop fault model, and certainly describes a number of failures that we see every day. However, especially in networked systems, this isn’t the only way in which nodes crash. They may instead, upon encountering a fault, crash and then recover from the fault, to begin executing happily from the point that they left off (remember that, with stable storage that persists between crashes, there’s no reason that a restarted node couldn’t simply pick up the protocol from where it crashed). This is the fail-recover fault model, which is more general than fail-stop, and therefore a bit more tricky to deal with.

To see how this could be a problem, imagine what happened if the co-ordinator in a 3PC run failed before it had received ‘prepared-to-commit’ replies from all participants (although all the replies were sent). During the failure, a recovery co-ordinator would be expected to take over, and in the scenarios we’ve described, shepherd the protocol run to its conclusion. The recovery co-ordinator would interrogate the participants, find that they were all ready to commit, and instruct them to the go ahead and commit the transaction.

At the same time, the failed co-ordinator recovers and resumes from where it left off. It notices that it hasn’t received ‘prepared-to-commit’ messages from all the participants, and times them out, sending a message to all participants to abort the transaction. However, these messages get interleaved with the commit messages sent by the recovery co-ordinator such that some nodes see the ‘commit’ message first, and some see the ‘abort’. The result is an inconsistent state - some participants have committed, and some have not.

You might not yet be convinced that this represents a real problem. Why could the failed co-ordinator not realise that it had failed, and remove itself from the protocol? The answer is that detecting failure, even your own, is not always easy to do. ‘Failure’ in this case is actually the failure of the co-ordinator to respond to messages within a set period of time (which causes the recovery co-ordinator to take over) - it does not necessarily describe a machine crash. Heavy processing load can cause a co-ordinator to delay processing a message for an arbitrarily long period of time. Similarly, heavy network load can delay the delivery of a message for an arbitrary period. In a synchronous network model, there is a bound on the amount of time a remote host can take to process and respond to a message. In an asynchronous model, no such bound exists. The key problem that asynchronicity causes is that time outs can no longer be reliably used as a proxy for failure detection: there is always a possibility that a host was just running slowly, and will respond the moment you declare it dead. Similarly, you can’t tell it, or anyone else, that it’s dead in time to stop it interfering with your recovery mechanism.

The fail-recover fault model neatly describes faults that may occur in an asynchronous network that wouldn’t exist in a synchronous one. 3PC, as I have described it, is not resilient against these faults. It in fact only works well in a synchronous network with crash-stop failures. Real networks aren’t like this - machines suffer heavy load, packets are lost, duplicated and delayed and in general we can’t say much about network timings.

So we need another consensus algorithm to cope with these problems. This is where Leslie Lamport came in, with his Paxos protocol which was discovered and made famous in the 1990s. Paxos was the first correct protocol which was provably resiliant in the face asynchronous networks. Remember that we must view all consensus protocols in the context of the FLP impossibility result which tells us that no protocol will be correct in all executions with an asynchronous network. Paxos withstands asynchronicity and waits it out until good behaviour is restored. Rather than sacrifice correctness, which some variants (including the one I described) of 3PC do, Paxos sacrifices liveness, i.e. guaranteed termination, when the network is behaving asynchronously and terminates only when synchronicity returns.

The major events in the development of consensus protocols can be summarised below, in hugely oversimplified form:

- Jim Gray (amongst others) proposes 2PC in the 1970s. Problem: blocks on failure of single node even in synchronous networks.

- Dale Skeen (amongst others) shows the need for an extra, third phase to avoid blocking in the early 1980s. 3PC is an obvious corollary, but it is not provably correct, and in fact suffers from incorrectness under certain network conditions.

- Leslie Lamport proposes Paxos, which is provably correct in asynchronous networks that eventually become synchronous, does not block if a majority of participants are available (so withstands \(n/2\)faults) and has provably minimal message delays in the best case.

Paxos in detail

Terminology

The actors in an instance of the Paxos protocol are familiar from 2PC and 3PC. One node acts as a proposer, and is responsible for initiating the protocol. Only one node can act as proposer at a time, but if two or more choose to then the protocol will (typically) fail to terminate until only one node continues to act as proposer. Again, this is sacrificing termination for correctness.

The other nodes which conspire to make a decision about the value being proposed are called, in Paxos terminology, ‘acceptors’. Acceptors respond to proposals from the proposer either by rejecting them for some reason, or agreeing to them in principle and making promises in return about the proposals they will accept in the future. These promises guarantee that proposals that may come from other proposers will not be erroneously accepted, and in particular they ensure that only the latest of the proposals sent by the proposer is accepted.

‘Accept’ here means that an acceptor commits to a proposal as the one it considers definitive. Once a majority of acceptors have accepted the same proposal, the Paxos protocol can terminate and the proposed value may be disseminated to nodes which are interested in it (these are called ‘listeners’).

The protocol

In skeleton form, Paxos looks very much like 2PC. The proposer sends a ‘prepare’ request to the acceptors. When the acceptors have indicated their agreement to accept the proposal, the proposer sends a commit request to the acceptors. Finally, the acceptors reply to the proposer indicating the success or failure of the commit request. Once enough acceptors have committed the value and informed the proposer, the protocol terminates. However, the Paxon devil is in the details of when an acceptor may accept a proposal, and what value the proposer is allowed to eventually request for acceptance.

Paxos adds two important mechanisms to 2PC. The first is ordering the proposals so that it may be determined which of two proposals should be accepted. The second improvement is to consider a proposal accepted when a majority of acceptors have indicated that they have decided upon it. This is different from 2PC where proposals were accepted only if every acceptor agreed to do so. This lead to the blocking characteristics of 2PC, where a single failed node could lead to the protocol never terminating while the proposer waited for a reply that would never come. Instead, in Paxos, nearly half the nodes can fail to reply and the protocol will still continue correctly.

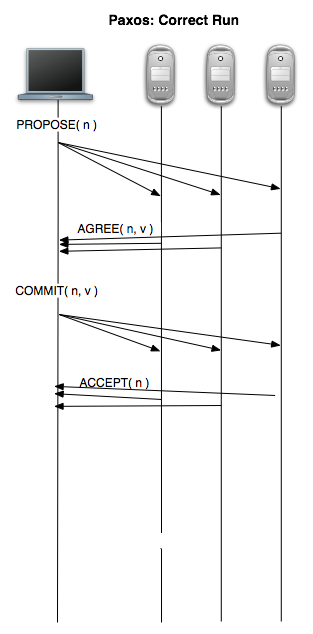

A failure-free complete execution of Paxos

Sequence numbers

Every proposal is tagged with a unique sequence number that we assume can be generated by any proposer. These sequence numbers are used to totally order the proposals so that all the acceptors agree on which proposals came ‘before’ and ‘after’. When a proposal arrives, the acceptor checks to see what the highest numbered proposal that it has already received is. If the new proposal is ordered after the highest current proposal, the acceptor returns a promise that guarantees that the acceptor will not accept any more proposals that are ordered before the new proposal. If instead the new proposal is ordered before the highest current proposal the acceptors will reject it and return the sequence number of the current proposal. This allows the proposer to choose a large enough sequence number at the next time of asking, rather than having to guess.

This ordering is used so that no matter what order the messages containing the prepare requests arrive in, the acceptors can agree - without further communication - on which one to agree, tentatively, to accepting. This helps cope with one of the artifacts of an asynchronous system - the possibility of messages arriving in different orders at different hosts.

How can we ensure that all proposals are uniquely numbered? The easiest way is to have all proposers draw from disjoint sets of sequence numbers. In particular, one practical way is to construct a pair \((seq. number, address)\) where the address value is the proposer’s unique network address. These pairs can be totally ordered and at the same time all proposers can ‘outbid’ all others if they choose a sufficiently large sequence number.

Majorities

One simple fact helps us understand how we can not require agreement from all acceptors and yet still call our protocol correct: any two majority sets of acceptors will have at least one acceptor in common. Therefore if two proposals are agreed to by a majority, there must be at least one acceptor that agreed to both. This means that when another proposal, for example, is made, a third majority is guaranteed to include either the acceptor that saw both previous proposals or two acceptors that saw one each.

This means that, no matter what stage the protocol is at, there is still enough information available to recover the complete state of all proposals that might affect the execution. Collectively, a majority of acceptors will have complete information and therefore will ensure that only legitimate proposals are accepted.

Legitimate proposals

Once the proposer receives responses to its prepare message from a majority of acceptors, it can go ahead and ask the acceptors to commit to a value it proposes. Again, this is very like 2PC, except again there are constraints on which values a proposer may legitimately propose. Remember that there are potentially many proposers proposing values at any one time. Consider the case where a proposer has committed his proposal to the smallest possible majority of acceptors, at which point a single acceptor fails. A majority of accept confirmation messages will not reach the proposer, and therefore the protocol will no terminate. A second proposer might then try to propose a value - which is accepted by a majority since the proposer orders its request after the first. The second proposer then commits its proposal, and a majority of acceptors respond. The second proposer considers the protocol completed. At this point, the failed acceptor can recover and send the final accept message to the original proposer, which then considers the protocol completed. If the first and second proposer both propose different values, correctness is violated. This is a problem.

This execution cannot be avoided in an asynchronous network. Therefore, the only way around is to somehow make sure that both proposers propose the same value. This avoids the complications above by ensuring that all committed values are the same at every acceptor - no matter which proposer proposed them. It’s easy to ensure that all proposed values are the same. When acceptors respond to a prepare request, they reply with the value of the highest numbered proposal that they have already accepted. The proposer is then bound only to ask that this value be committed. This way the protocol informs the proposer about other completed proposals, and forces it to commit their values, not the one it originally proposed.

Note that this doesn’t violate any of our requirements for consensus. We do not care which value is eventually accepted, and neither do the proposers, as long as it was originally proposed by some proposer. The acceptors are allowed to express an opinion by responding positively or negatively to the prepare request, but once a majority have agreed to accept a value, that’s the value that’s going to be accepted.

By having a majority of acceptors respond to every prepare request, Paxos ensures that every majority reply to a prepare request will contain a response from an acceptor that has seen each previously agreed proposal. Therefore before the proposer begins the commit phase, it is guaranteed to know what the value of the highest numbered previously accepted proposal is. This gives as an inductive guarantee that all accepted proposals will be for the same value. The sequence numbers also help out here. Acceptors, when they agree to a proposal, promise not to accept a value that is proposed as part of any proposal numbered less than the current proposal. This prevents a possible problem when a proposer with a low sequence number gets its proposal accepted between a higher numbered proposal being agreed (at which point the proposer of the higher numbered proposal is told about all previously accepted values) and being committed with a potentially different value.

The precise protocol

Informally, here are the steps that each principal in the protocol must execute.

PROPOSERS:

-

Submit a proposal numbered \(n\) to a majority of acceptors. Wait for a majority of acceptors to reply.

-

If the majority reply ‘agree’, they will also send back the value of any proposals they have already accepted. Pick one of these values, and send a ‘commit’ message with the proposal number and the value. If no values have already been accepted, use your own. If instead a majority reply ‘reject’, or fail to reply, abandon the proposal and start again.

-

If a majority reply to your commit request with an ‘accepted’ message, consider the protocol terminated. Otherwise, abandon the proposal and start again.

ACCEPTORS:

-

Once a proposal is received, compare its number to the highest numbered proposal you have already agreed to. If the new proposal is higher, reply ‘agree’ with the value of any proposals you have already accepted. If it is lower, reply ‘reject’, along with the sequence number of the highest proposal.

-

When a ‘commit’ message is received, accept it if a) the value is the same as any previously accepted proposal and b) its sequence number is the highest proposal number you have agreed to. Otherwise, reject it.

Failure tolerance

Paxos is more failure tolerant than 2PC. Using majorities instead of total agreement ensures that the protocol is tolerant to up to half the acceptors failing. If we wish to withstand \(f\) failures, we need to provide \(2f+1\) acceptors. If the proposer should fail, we can arrange for another proposer to take over the protocol by issuing its own proposal. If the original proposer recovers, the rules about committing only previously accepted values and agreeing to proposals that are numbered higher than what have been seen before ensure that the two proposers can co-exist without the danger of violating correctness.

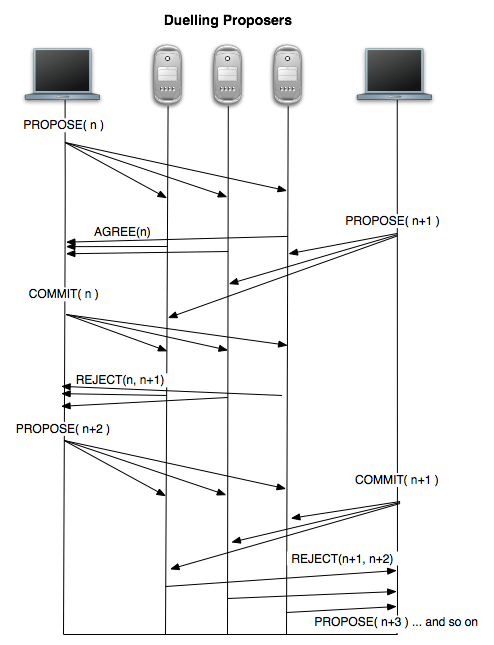

It’s easy to see that Paxos does have a failure mode. When two proposers are active at the same time, they may ‘duel’ for highest proposal number by alternately issuing proposals that ‘one-up’ the previous proposal. Until this situation is resolved, and a single leader is agreed upon, it’s possible that Paxos may not terminate. This violates a liveness property. However, the likelihood is that eventually Paxos will return to a correct execution once the network settles down and the two proposers observe each other and agree to let one go first (note that this isn’t quite the same as solving consensus: one proposer simply has to back off for sufficiently long to let the other proposer get its proposal committed).

Duelling proposers violate termination

There are other ways that Paxos can go wrong. Acceptors need to keep a record of the highest proposal they have agreed to, and the value of any proposals they have accepted, in stable storage. If that storage should crash then the acceptor cannot take part in the protocol for fear of corrupting the execution (by effectively lying about the proposals it has already seen). This is a kind of Byzantine failure, where an acceptor deviates from the protocol. Tolerance to generalised Byzantine failures is complex and difficult to make efficient (the established method is to add another \(f\) acceptors to out-vote the potential \(f\) that might fail Byzantinely.)

Efficiency

In an ideal correct execution of Paxos, message counts are low. In the first phase a proposer will send \(f+1\) messages, and receive \(f+1\) replies. This will be repeated in the second phase for a total of \(4f+4\) messages, with a total of 4 message delays. However, if a single acceptor fails, the protocol will take longer to complete as the proposal must be reissued. Instead the proposer might broadcast its messages to all \(2f+1\) acceptors, which implies that \(f+1\) would have to fail before the protocol is delayed. Of course, if the proposer fails, there is a delay while a) another proposer decides to take over and b) a new instance of the protocol is executed.

If the right sequence of failures occur, or if proposers go into duelling mode as described above, the message count could be arbitrarily large. Once the network returns to stable conditions, however, the delay until the protocol is completed is once again 4 message delays.

We should also factor in the cost of writing to disk at the acceptors and potentially at the proposers as well. Disk delays can be significantly larger than network delays, and the protocol is only correct if the disk write is guaranteed to have succeeded before a response is sent; therefore disk writes are also on the critical path.

Conclusions

This article has presented the basic Paxos consensus protocol and given a rationale for some of the design decisions that seem arbitrary or confusing at the first pass. There are a number of optimisations that may be applied to Paxos to arrange for fewer message delays in the ideal case and a shorter start-up time. I hope to outline these in a future article.

After the short coda below, I’ve included a (by no means comprehensive) bibliography for those who want to really pin the protocol down.

Coda: The history of Paxos

The history of Paxos is relatively colourful for a distributed protocol. Leslie Lamport discovered the algorithm in the late 1980s, born from an attempt to prove the corresponding negative result, i.e. that there was no such algorithm which satisfied Paxos’ safety and liveness properties. The harder he tried the more the result seemed to elude him until it became clear that he was actually constructing a working protocol.

He then wrote a paper and submitted it to Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS). If the paper had been dry and colourless, the story would end there. However, Lamport had presented the work as solving the problem of achieving consensus on measures voted for by a rather lazy parliament on the ancient island of Paxos. Lamport already had form for describing his work through analogy with the Byzantine Generals paper, and felt a similar approach would be successful here. Instead, the referees demanded the removal of the “Paxos stuff”, and Lamport, rather than comply, let the paper sit in his filing cabinet. However, the protocol began to gain some popularity through word of mouth, and via a much more formal (and lengthy) paper written by De Prisco, Lynch and Lampson. Lamport resubmitted the paper some eight years after the original attempt, and TOCS published it at the second time of asking in nearly its original form.

The published paper makes clear the connection with computer networks, and while working through an extra level of indirection makes the already subtle algorithm a little harder to grasp, it is by no means obfuscated by the presentation (which is playful and a welcome change from the usual theoretical computer science paper).

Still, it seems that it was generally found difficult to understand. When luminaries such as Nancy Lynch have difficulties with a paper, we mortals can feel a bit better about failing to grasp the context. Eventually, Lamport was moved to published “Paxos Made Simple” - a very short paper whose tone belies the author’s disappointment that the Paxon gambit didn’t quite pay off.

“The Paxos algorithm, when presented in plain English, is very simple.”

Since then Paxos has become well known, partly thanks to its popularisation by Google as a central part of its Chubby stack. Getting the protocol right in practice is hard, as explained in Google’s “Paxos Made Live”. There have been a few variations on the basic protocol, perhaps the most significant is multi-Paxos which allows requests to be chained together to cut down on the message complexity.

(The full version of events, from Lamport’s perspective, is on his writings page).

Bibliography

Paxos Made Simple

Presents Paxos in a ground-up fashion as a consequence of the requirements and constraints that the protocol must operate within. Short and very readable, it should probably be your first visit after this article.

The Part-time Parliament

The original paper. Once you understand the protocol, you might well really enjoy this presentation of it. Contains proofs of correctness which the ‘.. Made Simple’ paper does not.

Paxos Made Live

This paper from Google bridges the gap between theoretical algorithm and working system. There are a number of practical issues to consider when implementing Paxos that you might well not have imagined. If you want to build a system using Paxos, you should read this paper beforehand.

Cheap Paxos and Fast Paxos

Two papers that present some optimisations on the original protocol.

Consensus on Transaction Commit

This short paper by Lamport and Jim Gray demonstrates that 2PC is a degenerate version of Paxos that tolerates zero failures. This is a readable introduction to Paxos and motivates, like I have done, the protocol as an improvement over the extant 2PC.

How To Build a Highly Available System Using Consensus

Butler Lampson demonstrates how to employ Paxon consensus as part of a larger system. This paper was partly responsible for ensuring the success of Paxos by popularising it within the distributed systems community.